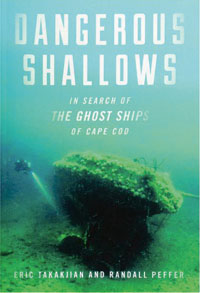

“Dangerous Shallows: In Search of the Ghost Ships of Cape Cod,”

by Eric Takakjian and Randall Peffer. Lyons Press, 2020; 256 pp.

Review by Sandy Marsters

On any given day, there just may be at least as many vessels on the bottom of the waters surrounding Cape Cod as there are floating on top. Of course, they’ve had centuries to pile up down there, but if they were all to magically pop to the surface at once the seas would suddenly be very crowded with every imaginable kind of vessel.

On any given day, there just may be at least as many vessels on the bottom of the waters surrounding Cape Cod as there are floating on top. Of course, they’ve had centuries to pile up down there, but if they were all to magically pop to the surface at once the seas would suddenly be very crowded with every imaginable kind of vessel.

Le Magnifique, a 176-foot French man-o-war would pop to the surface near Lovell’s Island in Boston Harbor from the spot where, laden with gold, she ran aground and sank in 1782.

Near Nantucket Island, the magnificent 690-foot Italian trans-Atlantic steamship Andrea Doria, would come to the surface at the spot she sank on July 26, 1956, after colliding with another liner, the Stockholm, in heavy fog.

Off Cohassett, up would come the collier SS Allentown, lost during a monster hurricane in November 1888 on her way from Philadelphia to Salem carrying a crew of 18 men and 1,660 tons of coal. Also popping to the surface would be a line of 15 ships spread over 30 miles, from Scituate to Boston, which went to the bottom in that same storm.

There would be German subs and the ships they sank; a huge modern bulk carrier; and, about 10 miles east of Boston, up would come a remarkable collection of ships including wooden tugs, passenger ships, barges, a Great Lakes freighter, a World War I destroyer escort, 64 ships in all, dragged from Boston Harbor as derelicts in the ’30s and ’40s and scuttled in a WPA project.

What a sight. Of course no such magic is going to happen, so there they will stay, out of sight. But not to everyone.

“Dangerous Shallows” is the story of some of the wreck hounds, like co-author Eric Takakjian, who have dedicated their lives – and in the process risking their lives, and too often losing their lives – in the quest to dive on and document these wrecks.

Treasure is one lure for these divers, but despite the occasional mother lode of gold or silver, riches are elusive. And wreck diving is an extremely expensive pastime.

Mystery and romance are also an allure. These divers see themselves as investigators, historians, scientists, technicians and archivists. They are a mix of tough guys, daredevils, highly disciplined mariners and divers who at the same time come off as sentimental and deeply in touch with the tragedies to which they are witnesses.

At the site of the sinking of the 397-foot MV Oregon on Dec. 10, 1941, at Nantucket Shoals, with the loss of 15 lives, Takakjian feels the weight of this work and gathers his crew.

“Something feels sacred about this place. Sacred like the wreck of the ghost ship we found on Georges Bank during our first trip out here. Sacred like the bones of the City of Columbus. Sacred like do not disturb. So as we stop over the wreck of what is surely the Oregon and drift above the graves of a bunch of all-but-forgotten merchant mariners, I tell the crew the story of this lost ship, her men, and their bad luck.”

“This is how we remember them,” he writes. “We tell their stories.”

Takakjian is particularly haunted by the memory of a woman’s shoe he found on what he calls “One of the most haunting dives of my life.”

At other times, though, the work of these divers can seem crass, cold and greedy. Perhaps there is a code among wreck divers that justifies what at times looks to the observer a lot like looting. If there is such a code, it would be good to make it clear to the reader.

Overall, this is a book of adventure on a grand scale. It is not just about the dive, but spends time also on the circumstances of each tragedy. These are set off in italics to distinguish them from the overall narrative, and the results provide some nail-biting drama that the writers have pieced together from historical records.

From time to time, the flow of the book can be confusing as the writers switch randomly between present and past tenses.

In one scene, “Many stayed up to socialize, drink tea, or quaff distilled spirits. Others play cards in the main saloon . . . .”

This construction can be confusing and disorienting.

Nevertheless, “Dangerous Shallows” is in the end a book you will not want to put down. Through the eyes and minds of the divers, barring a miracle, it is the only way the rest of us will ever get to see these historical treasures.

Co-founder of Points East, along with Bernie Wideman, Sandy Marsters is also the magazine’s former editor.

We have complete issues archived to 2009. You can read them for free by following this link.

We have complete issues archived to 2009. You can read them for free by following this link.